Making the walls quake as if they were dilating with the secret knowledge of great powers

Polish Pavilion at the 13th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia Common Ground

28 August–25 November 2012

comissioner of the Polish Pavilion: Hanna Wróblewska

curator: Michał Libera

cooperation: Joanna Waśko

sound design: Ralf Meinz

interior acoustician: Andrzej Kłosak

Main composition (excerpt)

Opening performance

Biennale Jury Report: “Special mention goes to Poland for ‘Making the walls quake as if they were dilating with the secret knowledge of great powers’. This brave and bold installation reminds the visitor to listen as well as to look… And to feel the sound of the Common Ground.”

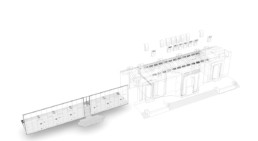

The sound sculpture showcased the Polish Pavilion as a listening system, as an original system of listening to (for) us: producing, transmitting and distorting sounds. In cooperation with neighbouring pavilions (Egypt, Serbia, Venice, Romania), sound there amplified reached the Polish Pavilion. An installation was produced on the basis of detailed measurements, underlining acoustic properties of the Polish Pavilion. Sound was used to map out acoustic faults of the building, but also to intensify psycho-acoustic impressions accompanying a visit to the sculpture. Vibrations produced by the building were explored and amplified, thanks to which a quaking of the Polish Pavilion, including that of its ventilation system, as well as noises of everyday activities performed by neighbours were made audible.

Acoustic measurements revealed a lengthy reverb, as long as six seconds. In the empty room of a surface smaller than 200 m2, human speech becomes incomprehensible, even at a distance of three metres from a source of its emission. This is caused not by a low volume, but by the long reverberation. To emphasise the phenomenon, the room’s resonating frequencies were amplified, which further depleted the ability of speech comprehension and made even a regular conversation difficult.

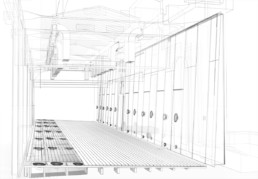

Original materials used in the pavilion (bricks, marble) as well as its symmetrical shapes and rectangular forms cause the sound to be reflected, while remaining at the same, horizontal level. In such case, a localisation of sound sources becomes practically impossible. Voices appear to come from everywhere, even if, in reality, they are emitted behind a listener’s back. An impression of all-encompassing sound was reinforced by a minimal bending of a wall and the floor. An introduction of a new material – a wooden floor – also affected sound propagation. Fifty sources of sound rendered the effect of sound confusion all-embracing.

To restore proper circulation in the ventilation system, a suspended ceiling, which had been affixed there for a number of years, was disassembled. The disassembly revealed that words spoken through ventilation openings in the roof are more comprehensible than those emitted from the floor level. In this sense, revealing its ventilation system opened up the pavilion to its environment, including the other pavilions from which sounds originated. For the purpose of the sound sculpture, ventilation pipes were used for introducing the sound of the surroundings alongside air conveyed.

Acoustic analyses revealed a walled-in apse, situated opposite the entrance to the pavilion, missing from its architectural plans. The apse is displayed in the exhibition in full glory, and the sound sculpture restores its fundamental acoustic function, or reflecting of sound entering through the vestibule into the centre. The vestibule itself symbolises passing from the exterior to the building’s interior, which was emphasised by muffling and a radical noise reduction in this section of the building. The vestibule is also an invitation to an aural experiencing of the sculpture.

The ultimate gesture was a sonification of walls of the building, a transformation of vibrations of solids into vibrations of acoustic waves. Thus, tremors of the building became audible, together with selected spaces of its interior. A network of sensors and cables encircling the whole building – facades of all the other pavilions – appears by means of underlining the continuity of sound as a phenomenon of vibration. Architectural micro-intervention demonstrated consequences of the architect’s decisions for an experience of the space, both in its physical and social dimension.

Every architecture is an acoustic phenomenon – it forms an environment for sound propagation, reinforces some of its properties at the expense of others, and also absorbs it, filters and transmits. In a discreet and invisible manner, it, thereby, organises social life. A sonic perspective allows to discuss the process in terms other than separation and delimitation of social spaces. Walls, floors, ventilation, heating or sewage systems – are all systems of connecting and transforming interpersonal relations, rather than their disjunction. We keep hearing others and we are audible to them, listening to, eavesdropping on them – often despite, and sometimes even against our own will – or triggering other procedures of listening through architecture.

The piece was dedicated precisely to such practices of listening; hence, to a function of architecture in laying out the titular ‘common ground’ at a sonic level.

Thanks to its evanescence, invisibility and impalpability, but also due to its intimate and physical nature, the piece became a metaphor of the present – suffused with anxiety mixed with a simultaneous, compulsive desire for contact and connection with other people. The exhibition was accompanied by a publication.

[description based on a curatorial text]

The exhibition is accompanied by a multidisciplinary reader on sound, space and architecture with texts selected by Lidia Klein and the curator of the exhibition, Michał Libera and designed by Czosnek Studio. The book features an interview with Katarzyna Krakowiak, contributions by the curator, the editors, as well as a selection of theoretical analyses, essays, poems and music scores. It is divided into three sections: “Sound in architecture: reverberation”, “Sound through architecture: eavesdropping” and “Sound of architecture: vibration.” The volume brings together texts by Mark Bain, Karin Bijsterveld, Barry Blesser and Linda-Ruth Salter, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Francis Bacon, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Steve Goodman, Bohumil Hrabal, Branden Wayne Joseph, Eric La Casa, Bernhard Leitner, Francisco López and Klaus Schuwerk, Alvin Lucier, Florence McLandburgh, John L. Locke, Max Neuhaus, Georges Perec, Steen Eiler Rasmussen, Bruce R. Smith, Jonathan Sterne, Georges Teyssot, Emily Thompson, Thomas Tilly and Jean-Luc Guionnet, Lamberto Tronchin, Shelley Trower, Toshiya Tsunoda, David Toop and Paweł Mościcki.

Photos: Krzysztof Pijarski